The Digital Spotlight: Applying a Connective Action Framework of Political Protest to Global Watchdog Reporting

Before the Covid-19 pandemic, the last major tranche of newsroom job cuts occurred with the shift to a digital economy, further exacerbated by the Global Financial Crisis of 2007-09.

During these disruptive times, digital technologies were both a curse and opportunity for newsrooms. Much was written about the curse: the financial duress for established media outlets as audiences and advertising revenues migrated to the online technological giants.

As advertising was decoupled from journalism, many mastheads closed their doors, some after more than a century of operation. In Australia, the ripple effect of the GFC hit when News Corp, Fairfax Media (now Nine) and Channel 10 shed about 3000 jobs in June 2012.

Notwithstanding these significant challenges for news media, the digital age has also heralded opportunities for journalism. Among them, are innovative uses of technology and collaboration to produce large-scale transnational investigative reporting.

In a just published article in the International Journal of Press Politics, I investigate how newsrooms and reporters have adapted to austere times to continue to produce quality investigative journalism on a global scale, not previously achieved.

These adaptations have included collaborations with other media companies and non-media organisations such as NGOs and academia, as well as the clever use of digital technologies, big data and social science methods to tell stories of global importance.

In many cases, perhaps in a backlash to surveillance capitalism, the data is anonymously leaked.

Think of the International Consortium of Investigative Journalist’s (ICIJ) 2016 reportage of the Panama Papers. In this example, almost 400 journalists from more than 80 countries worked together in secret for a year using shared digital technologies to analyse the 11.5 million leaked files from Panamanian law firm Mossack Fonseca. Their joint mission was to tell the story of how elites and the rich had avoided paying tax using offshore tax havens.

Through transnational collaborative investigative journalism, the digital spotlight was shone on the global discourse about tax fairness. This debate was amplified through myriad instances of newsrooms’ local reporting of tax evasion stories and public engagement using social media platforms and customized digital tools.

Another transnational example of investigative journalism was WikiLeaks’ access to soldiers’ personal accounts of the Iraq and Afghan wars. These stories shared and verified by journalists from The Guardian, The Age, Der Spiegel and elsewhere, detailed the uncharted deaths of civilians and true cost of war.

A third case is the leaked National Security Agency files by whistle-blower Edward Snowden. Working with a film maker, and investigative journalists from The Guardian and Washington Post, the public learn how their democratic governments spied on them without their knowledge or consent.

In each example, investigative reporters have collaborated with others to analyse and find patterns in leaked data to expose widespread wrongdoing. These collaborations have required a seismic shift in the way newsrooms think and operate. The old model of single newsrooms fiercely competing with one another for stories has shifted to a new model whereby journalists from disparate newsrooms work together to expose transgressions against the public interest.

Yet, with notable exceptions, there is little theorisation about the methods and processes of large-scale collaborative investigative reporting, or its impact on global debates.

Drawing on communications and political science scholarship, my research aimed to develop a conceptual framework for understanding different forms of large-scale investigative reporting. My study builds on Lance Bennett and Alexandra Segerberg‘s 2013 book-length study of different types of political protest entitled: The Logic of Connective Action: Digital Media and the Personalization of Contentious Politics.

Their framework distinguished between more traditional forms of political action such as collective action principally led by organizations like trade unions, and newer forms of mass protest that bring together individuals (and organizations) with a less hierarchical power structure that they term connective action. In connective action models, digital media technologies are key to organising and communicating the protest action. Examples include the 2011 global Occupy protests and the 15-M movement in Spain.

Bennet and Segerberg’s framework provided a useful starting point to understand different types of large-scale investigative journalism because, like political protest movements, journalism networks can: produce record-breaking mobilizations; show flexibility in terms of political targets and issues; use shared content to relay personal perspectives, and undertake their own software development to support their networks.

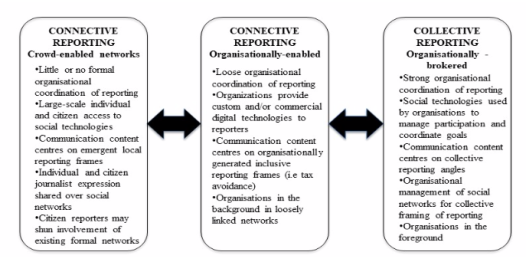

Furthermore, different architectures of power exist within journalism networks, just as they do in different networks of contentious politics. In Figure 1, I adapt Bennett and Segerberg’s framework to apply it to large scale investigative reporting.

Figure 1: Features of different types of large-scale collaborative investigative journalism.

Through interviews with investigative reporters and secondary data, I show how the reportage of the Panama Papers, WikiLeaks war logs and NSA leaks represent different types of large-scale investigative journalism. Like Bennett and Segerberg, I accept that there is ‘noise’ using a case study approach to define ‘ideal’ types of investigative journalism networks. I also acknowledge that the journalism network might shift from one organizational form to another as the power dynamics within a network might change. Indeed, this is observed with both the WikiLeaks and the Snowden cases.

Before it imploded, I argue that WikiLeaks began as an organizationally brokered reporting model, with it as the lead organization exercising a high degree of control (see Figure 1). But with the sharing of data with many more media outlets, power became more diffuse and, at that point, the network might be better categorized as an organizationally brokered connective model.

The Snowden NSA leaks also suggest an organizationally brokered connective reporting model led by The Guardian, that quickly became a crowd-enabled reporting model. The use of commercial digital networks such as social media sites, Facebook, YouTube, Twitter and others were central to the story’s global reach, with little formal coordination of mainstream media reportage.

What we learn from this framework is that whilst transnational collaborations may bring together disparate journalism actors with differing political ideologies, reporters themselves stress the need for trust relationships with fellow collaborators that are built on shared understandings of professional journalism values and norms, if the network is to endure. This might help explain why the WikiLeaks collaboration ultimately fell apart.

The success of these large-scale investigative journalism networks is that they are able to produce reporting greater than what any individual journalist, newsroom or organization could deliver by going it alone. Media and digital networks are central to the processes of globalisation this century, and journalists like other actors have enlisted network models to engender an emergent global sphere. Global debates about tax fairness, state surveillance of citizens, and the true cost of war show the flexibility of this collaborative journalism model to date.

Dr Andrea Carson is Associate Professor, Department of Politics, Media and Philosophy at LaTrobe University. This blog post is based on a recently published piece of the same title in The International Journal of Press Politics